“While you and I can perceive a wide range of colours, trees like our oak are only able to sense the red light in the spectrum and they can do this thanks to an incredible chemical pigment in their leaves called phytochrome. Phytochrome, a substance in our oak’s leaf cells, is incredibly sensitive to the red light that makes up part of the sun’s rays. It’s a kind of chemical stopwatch that is also able to measure the hours of sunlight and darkness. So, as nights get longer, the phytochrome acts like a signal, telling the tree that autumn has begun.”

— George McGavin, Oak Tree: Nature’s Greatest Survivor, 2015.

Perceiving Phytochrome.

Perceiving Phytochrome comprises a series of five large-format prints made using black and white infrared film and slow shutter speeds, to imagine the animacy and perception of trees. Phytochrome, a photoreceptor protein found in the leaves of trees, functions to respond to far-red light at the extreme end of the visible spectrum (light that is visually perceived by the human eye), to control multiple aspects of plant development. One component of this development is the growth, death and movement of leaves which can determine leaf growth and how they position themselves in relation to the sun, a phenomenon called “phototropism”. As far-red light exists just before infrared light and is only dimly visible to humans, I began to think of ways in which photography might be able to poetically visualise how oaks use their leaves to perceive, or “see”, their surroundings.

According to the research of ecologists such as Suzanne Simard (2020), Monica Gagliano (2018) and Stefano Mancuso (2021), a plant's ability to sensorily perceive the world around them is, rather than centralised to a particular organ like it is for humans, instead de-centralised and articulated throughout their entire bodies. To think, therefore, of trees “seeing” is to try and imagine arboreal sight from every point of their body all at once. A potentially blinding, chaotic view if such a view was translated into the action of the camera for it to be visually interpreted.

In an attempt to simplify this potentially chaotic view, Perceiving Phytochrome takes the leaf as its subject and conceptual focus. Using infrared film which makes light normally invisible to the human eye, visible, I began to think about how this might function as a metaphor to perform a bridge between human and plant perception. In essence making images through an entirely different electromagnetic spectrum as a creative strategy to invite the human into a (albeit humanly constructed) visual realm of plants, poetically placing us in “their” world.

To focus the project on a specific subject, I selected a mature oak tree that I passed by regularly on a walk to Park Wood in my hometown of Kington. The tree stands in the pasture grounds of Hergest Croft Estate and Gardens, together with, perhaps, their sibling oak who stands just a few meters away. Rather than focussing on a single view that captured the entirety of the oak like in Arboreal Encounters, I decided instead to make many photographs that could either be viewed separately or, when put together, would construct the oak’s likeness as a whole. This effectively expands the oak tree from the confines of one single image into several that articulates its body across a greater scale, producing an immersive visual environment.

Images from top-bottom include (in order) ‘Canopy, Trunk and Root’ of a Mature Oak in Hergest Croft Estate, Hergest Croft, Kington, U.K., from the series Perceiving Phytochrome as part of the practice-based PhD project ‘These Rooted Bodies: Photographic Encounters with Plant Intelligence and the English oak tree through Material, Theory and Practice’, 2024. Digital scans from 120mm negatives.

The images here are black and white, made using monochromatic infrared film in combination with a red filter lens that, in doing so, distorts the ways in which light is perceived and interpreted, either by myself, the camera or the infrared film. For example, as light responds differently on the infrared spectrum focal lengths must be compensated for in-camera, as what is in focus through the viewfinder may not be what ends up being in focus upon development. Because of this, I began to think about how such methods that seek to image non-human worlds end up distorting human vision in real time, meaning my traditional control of certain technical attributes of photography is disrupted.

As leaves are also productive, non-static components of a tree’s biology, slow shutter speeds that focussed on the leaves during a windy period were used to depict the tree as animate, memorialising a commonly held experience of seeing, and hearing, the rustle of leaves during a dynamic breeze, also called “susurration”. To explore this, slow shutter speeds that capture the effect of wind blowing through the tree’s canopy (inspired by John Blakemore’s ‘Lila’ and ‘Wind’ series) was used to consciously blur the leaves and imbue the images with a longer sense of time. As Blakemore says himself:

“The idea of photographing the wind contains a paradox, the photograph describes surface appearance, the wind is invisible. To depict the traces of the wind, movement etched in light, I evolved a method of multiple exposure. The relationship of the photograph to time was thus extended, became itself a process, a mapping of time, an equivalent of the process of the landscape itself.”

This combination of slow shutter speed and infrared film, therefore, serves as an intentional disruption of traditional views of the oak tree which portray and perceive them as passive or static. Printed as large-format prints that move vertically and horizontally across a single oak tree, Perceiving Phytochrome invites an immersive and disorienting perspective of trees not as organic statues, but instead as energetic forms of life.

The latter stages of development for Perceiving Phytochrome could not have happened without the support of a grant by the Richard and Siobhán Coward Foundation for Analogue Photography. The money received helped fund the infrared stages of the project and enabled the purchase of at home darkroom equipment.

“Having to adjust the camera to meet the demands of light visible to plants rather than of humans requires one to use their equipment differently. The additional distance placed between myself and the image I expect to make due to the technical structure of infrared photography is another fascinating effect of infrared that displaces human agency or control, in this case my own vision, without entirely abandoning it. As there is an attempt here to approach plants within their own visual spectrum, the fact that the photographic method chosen to do so contributes to a distortion of human vision is yet another symbolic effect of how centring the plant within photographic practice can destabilise the human. Trees are, in this way, very much of the place they inhabit. This can be also thought of holistically, in that they are vessels of cultural and social memory which are intrinsically bound to the place from which the memories arise or were experienced, but also in that they are a direct product of the soil and the atmosphere in which they are imbedded. They are, in this sense, a material and cultural embodiment of place (Cloke and Jones, 2011). However, although sessile and of place, both of which suggest fixity, neither are they static in their processes or functions. As much of their functionality, despite the very visible and familiar seasonal change, is hidden from human view or near invisible to the naked eye, part of the project’s intentions are to bring an awareness to the tree’s sensorial perception — to uncover and depict the tree’s engagement with place. Removing, in a sense, the shroud of plant blindness.”

— Epha J. Roe, notes on Perceiving Phytochrome, ‘These Rooted Bodies’, 2024.

‘Mature Oak Canopies, Hergest Croft Estate, Hergest Croft, Kington, Herefordshire’, from the series Perceiving Phytochrome as part of the practice-based PhD project ‘These Rooted Bodies: Photographic Encounters with Plant Intelligence and the English oak tree through Material, Theory and Practice’, 2024. Digital scan from 120mm negative.

Together, Perceiving Phytochrome is displayed as a grid, moving from the lower part of the tree (their roots) up through to the canopy (or their crown), and then across either side to their boughs. The effect attempts to mirror, and reference, the way the eyes might drift slowly upwards and across a tree of interest; the swirling blurs reminiscent of wind softly blowing through their leaves.

Installation photograph of Perceiving Phytochrome & Soil Circle (2025), as part of the solo show ‘These Rooted Bodies’ at RidgeBank Contemporary Art Space in 2025. The soil depicted was collected from the roots of the tree featured as the subject in Perceiving Phytochrome. As a slight (intentional) deviation from my traditional practice, Soil Circle was inspired by land artists of the 1970's whose direct intervention with the environment called into question our human relation with it. As many aspects of my encounter with oak trees between 2018-2025 included my physical engagement with soil (some of which made it into the material of photographs), it felt right to bring it back into the gallery as a main feature point. In our early conversations about the exhibition, Caroline Allen (curator at RidgeBank) suggested I gather soil from the base of the Hergest tree featured in Perceiving Phytochrome, bringing in another form of locality into the gallery space. The soil's placement upon a plinth directly in front of (and below) the tree from which it came further roots these physical and local connections — acting almost as if I've "returned" the soil back to its artistic counterpart in the gallery.

Special thanks to Julia Banks of Hergest Croft Estate for their generous permission to gather soil for this project.

Detail image of Soil Circle (2025).

Earth, stones, pebbles, roots, decaying plant matter, unknown vegetation and invertebrates.

Material collected from the roots of a mature Oak from Hergest Croft Estate, the subject depicted in the photographs of Perceiving Phytochrome.

Our Roots

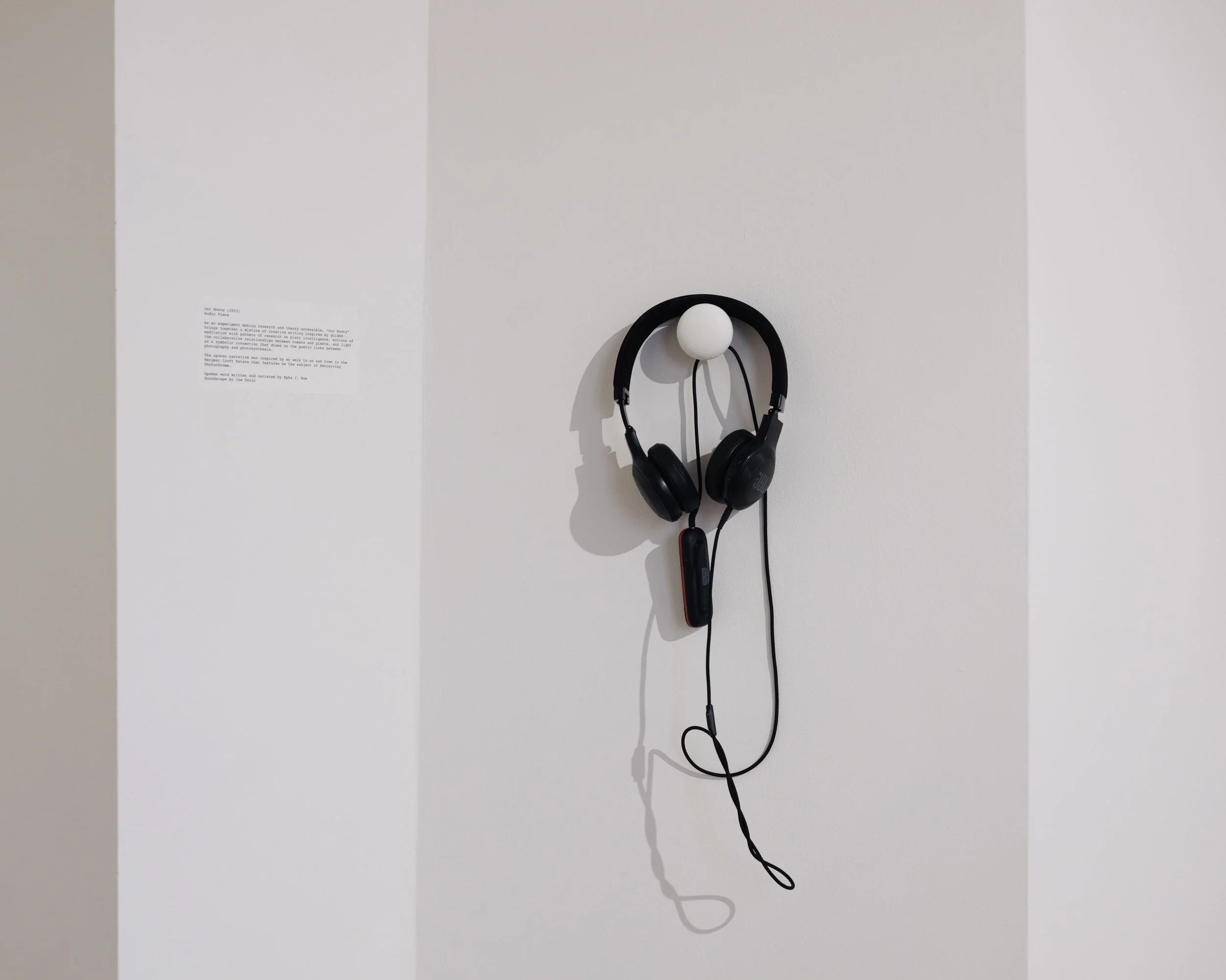

The audio here is a collaborative audio piece between myself and musician Joe Davin, made for the multimedia research and practice exhibition 'Roots: A Journey of Discovery into England’s Heritage Oak Trees', that took place at The Artery Gallery, Worcester, between 21st of July and the 2nd of August.

An experiment in the practice of disseminating research and theory in an accessible way, the piece brings together a mix of creative writing inspired by guided meditation with pockets of research surrounding ideas of plant intelligence and agency, notions of the collaborative relationship between plants and humans, and light as a symbolic connection that links together the action of the camera with the action of photosynthesis.

The narrative itself was inspired by my walk to the trees that feature as the subject of Perceiving Phytochrome. Therefore, if you require visuals to help guide your thoughts through the audio, please feel free too drift back up to the images.

Spoken word written and narrated by Epha J. Roe

Soundscape by Joe Davin

Installation image of the headphone set-up at RidgeBank Contemporary Art Space, Kington, for the solo show ‘These Rooted Bodies’, Aug-Sept 2025.